I have a new article in the May-June print edition of TAC titled, “The Art of Placemaking,” about the substance and impact of Camillo Sitte’s 1889 book, The Art of Building Cities. Sitte focused on site design for urban spaces, and remains one of the most important aesthetic analysts of traditional European urbanism. A quote:

I have a new article in the May-June print edition of TAC titled, “The Art of Placemaking,” about the substance and impact of Camillo Sitte’s 1889 book, The Art of Building Cities. Sitte focused on site design for urban spaces, and remains one of the most important aesthetic analysts of traditional European urbanism. A quote:

One of Sitte’s foremost concerns is the placement of monuments. Today, features like statues, sculptures, fountains, and obelisks may seem mere afterthoughts to core questions of urban planning. For Sitte, who considered the fine art of planning to extend down to the precise details of every urban space, such a presumption about ornament could not be more wrong. In his approach, the decision as to where a monument would be placed was as important as the choice of the object itself.

On his preference for irregularity in urban plans:

Always skeptical of overly rationalistic designs, Sitte is adamant about the value of irregularity. He contends that the modern desire for symmetry is misguided. Looking back to the history of the concept of symmetry, he writes:

Although [symmetry] is a Greek word, its ancient meaning was quite different from its present meaning…. The notion of identical figures to the right and left of an axis was not the basis of any theory in ancient times. Whoever has taken the trouble to search out the meaning of the word … in Greek and Latin literature knows that it means something that cannot be expressed in a single word today…. In short, proportion and symmetry were the same to the ancients.

For Sitte, the ancient meaning of symmetry is something closer to harmony than to a bilateral reflection. He argues that the more rigid definition is a product of Renaissance times that began to haunt the thinking of architects and planners, diverting them from the more nuanced harmonies of older, more irregular designs. Returning to the topic of public squares to apply this interpretive lens, Sitte notes that irregularities on the map are rarely discordant in actual experience. Instead, he contends that they can provide more interesting vistas, better proportioning, and even ideal sites for civic art:

The typical irregularity of these old squares indicates their gradual historical development. We are rarely mistaken in attributing the existence of these windings to practical causes—the presence of a canal, the lines of an old roadway, or the form of a building. Everyone knows from personal experience that these disruptions in symmetry are not unsightly. On the contrary, they arouse our interest as much as they appear natural, and preserve a picturesque character.

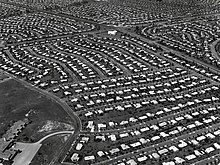

This point about urbanism is broadly consistent with Einstein’s famous observation that “The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science.” As Raymond Unwin and others have observed, curved streets create an inherent sense of mystery, because their vistas reveal themselves only gradually, as one’s movement changes one’s perspective. That which has not yet become visible, but which we intuit to be there, compels us forward and holds our attention as it does so. Compare this to a typical grid, where streets, in the words of T. S. Eliot, “follow like a tedious argument.”

A web version of the article is up now, as well. Read the whole thing, and enjoy!

Sad to report that a promising and important piece of legislation

Sad to report that a promising and important piece of legislation