Click on the above photo to see my full gallery!

Spotlight: The Old Jewish Lower East Side

New York From a Balloon, 1871

Woolworth: Cathedral of Commerice

A beautiful guidebook from 1920 (earlier versions were also published) to the “highest building in the world,” 233 Broadway, the Woolworth Building. Note the plate inside the cover: this copy came from the personal library of Seymour Durst!

Spotlight: Pierpont Morgan

Click on the above photo to see my full album!

The main building on this campus was J. Pierpont Morgan’s private house, and included an incredible private library, complete with mezzanines and bookshelves that turn to reveal hidden, spiral staircases. The architectural detail of this property, alone, makes it worth a visit. The displayed collection currently includes a Gutenberg Bible, an original manuscript by Mozart, and a painting by Leonardo Da Vinci’s teacher. J.P. Morgan was also an avid collector of cylinder seals from the ancient world (little spools of lapis lazuli, obsidian, or other hard materials, that were carved with a unique image and pressed into hot wax in order to verify the authenticity of a document or packaged good). Morgan became something of an expert on these, and many items from his collection are displayed. Fascinating stuff.

Where Will it Flood as Sea Levels Rise?

We hear more and more about the threat to coastal cities from rising sea levels. But being able to visualize the local spatial implications of this phenomenon brings it home in an entirely new way. One of the most interesting tools is the Surging Seas Risk Zone Map, from Climate Central, a Princeton-based independent organization that promotes public awareness about climate change. Here, you can search for any location, and visualize the contours of new shorelines with sea levels that have risen in increments of feet and meters.

Here’s a map of what would happen in the Newark Bay basin by 2100 if sea levels rose by more than two meters, as envisioned by a recent analysis of the potential loss of significant Antarctic ice sheets:

In this scenario, Newark Airport, the entire Seaport area, and much of the Ironbound has been flooded. In addition, Newark Bay appears to have swallowed up most of the salt meadows, and the blocks along the tidal portion of the Passaic River are under water. Finally, take a look at Hoboken and downtown Jersey City, on the far right: the Hudson River waterfront has essentially become a barrier island, while the blocks leading back toward the Palisades have been saturated.

Meanwhile, here’s a look at some of the coastal areas of New York City, under the same scenario:

The submerged areas on this map (e.g., the Rockaways, Coney Island, Howard Beach, Canarsie, Red Hook, and the South Shore of Staten Island) line up almost perfectly with the areas that experienced the most destruction from Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

Keep in mind that these maps offer a vision of what could happen with just a seven-foot (7′) rise in global sea levels, which is now being held out as a plausible scenario for 2100. Some of the projections to the year 2500 show global sea levels rising 49 meters.

Art Imitates Land Use: ‘Sunset: St. Louis’

Hushed in the smoky haze of summer sunset,

When I came home again from far-off places,

How many times I saw my western city

Dream by her river.

Then for an hour the water wore a mantle

Of tawny gold and mauve and misted turquoise

Under the tall and darkened arches bearing

Gray, high-flung bridges.

Against the sunset, water-towers and steeples

Flickered with fire up the slope to westward,

And old warehouses poured their purple shadows

Across the levee.

High over them the black train swept with thunder,

Cleaving the city, leaving far beneath it

Wharf-boats moored beside the old side-wheelers

Resting in twilight.

From Flame and Shadow (1920), by Sara Teasdale.

The Ghost Blocks of Manhattan

At the time of its adoption, the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 envisioned the eventual urban development of all the raw land that would become Central Park. Intersections that would never come to be — like West 64th Street and Sixth Avenue, or West 109th Street and Seventh Avenue — were surveyed and marked on the rural land of New York County.

At the time of its adoption, the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 envisioned the eventual urban development of all the raw land that would become Central Park. Intersections that would never come to be — like West 64th Street and Sixth Avenue, or West 109th Street and Seventh Avenue — were surveyed and marked on the rural land of New York County.

Recently, some physical evidence of the preliminary grid-platting has, quite literally, come to light in the right places. In a recent New Yorker article, Marguerite Holloway describes the discovery, and explains the origin of the mysterious markers in Central Park — as well as why they had disappeared and remained buried for nearly two centuries:

So the grid plan sank below the park, largely lost to the sculpted waves and undulations of landscaping. Just a few white marble pillars remain, marking a forgotten aspect of Manhattan’s original street plan, and evoking a wilder, emptier landscape in which white stones stand like cairns.

What Makes Property Private?

Stones once set off private property. Photo: John Fielding. Used with permission.

In a piece called, “This Land Is Your Land. Or Is It?” Justin P. McBrayer uses the occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon as a jumping-off point to question some of the most pervasive assumptions about private property, including how it comes to be, and the moral standing of one’s claim to ownership. Challenging the idea that history illuminates claims, he writes:

What are the chances that the money you used to buy your phone can be traced backward through your employer, your employer’s customers, and so on back through history without passing through the hands of a serious injustice? Slim to none. The same can be said for the seller’s side of the transaction. Chances are excellent that your phone arrived in your hand only after the exploitation of workers, abuse of the environment, theft, fraud, human trafficking, or any number of deal-breaking injustices.

This is true. It is especially true of currency, which passes through so many iterations of title, often in short periods of time. But even with tangible or intellectual property, and especially with land, a good number of today’s titles were created or have changed hands since their creation via some form of trickery or theft. Knowing this to be the case, one of the major challenges of property law is to determine when, if ever, the law should throw its weight behind a private claim to ownership. One could make the argument that the presumption ought to be against such claims; that the burden of proof should fall on the person in possession who seeks to claim anything more than mere possession. To some extent, this burden already exists. Buyers take title at their own peril, hence, the need for title insurance. But the burden could be greater. Good title, itself, could have to be proven against the presumption of historical wrongs, before it could vest. That is to say, the moral rationale that underpins legal title could have to be proven by the one claiming ownership.

One inevitable result of such an approach would be to have much more property in common ownership. That is to say, such a burden would be so difficult to meet that, were it to be established as a requirement, nearly everything in private hands would default to the commons. From a socialist viewpoint, this mass erosion of title might seem desirable, providing as it would a basis for tearing down claims to private property that are undoubtedly dubious, but that nonetheless, because they are supported by legal presumptions, provide the basis for real economic and political power in the present time. But, as with most attempts to legislate an ideal, such a structure would present its own host of difficulties through its intrinsic conflicts with human nature. The human propensity to fight over property creates powerful incentives for the law to sanction and settle who has title to what, without necessarily examining the immemorial chaos that has gotten us to the status quo. By decisively recognizing titles, and presuming that possession can be equated, in most cases, with recognizable ownership, the law averts an infinite number of potential conflicts, and creates incentives for individuals to acquire wealth peacefully, rather than by force.

This compromise, like most law, remains both logically and morally imperfect. But, so what? If, as Holmes famously remarked, the path of the law is experience, not logic — that is, if there is no perfect answer to the power struggles that characterize life within civilization that can be reconciled with what we know of human nature — then why shouldn’t practicability have the last word on these matters, at least when what is most practicable is not in direct conflict with any fundamental moral consensus? From such an angle, the current system of private property titling is actually quite defensible, so long as there is sufficient opportunity in the marketplace for those who act legally and peacefully to acquire enough private property for the system of incentives to work. With this caveat, the system largely keeps the peace and provides incentives for individuals to work, invest, and improve their property. The practicable imperative, therefore, is not to divest a large number of economic stakeholders of their admittedly dubious but nonetheless socially stabilizing claims; it is to ensure that enough economic opportunities exist for others, still in line, to ensure that existing claims do not become the obsessive objects of jealousy and scrutiny.

Land Use Imitates Art

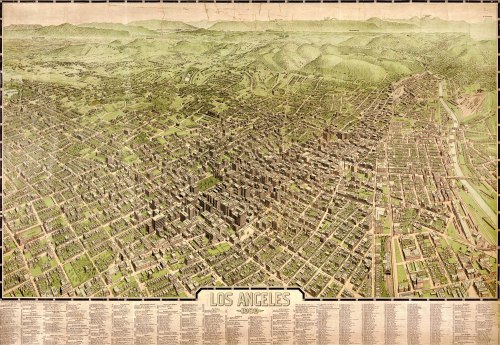

Here’s a three-dimensional, color map of Los Angeles, in 1909. It’s interesting. You can see the urban core that was beginning to take shape: the concentration of zero-lot line buildings, the canyons of concrete, the traditional green squares, the grid of warehouse blocks near the railroad tracks. Had it not been for the interruption by history — motor vehicles, modern zoning — a more traditional big city might have evolved there.

Here are a couple of surviving examples that I found of urban fabric in the core of Los Angeles, from which you could kind of envision an alternate pattern of how Southern California might have developed:

Broadway / 7th Street, Los Angeles.

Spring / West 4th Streets.

Just north of the urban core is Bunker Hill. You can see it in the bird’s-eye view, above, where the land rises behind the dense grid of streets, and the structures transition from commercial to residential. Most of what was once there is gone today. Here’s an old photograph, looking across Pershing Square:

Raymond Chandler described the late stages of the neighborhood’s decline in his 1942 novel, The High Window, as only he could do:

Bunker Hill is old town, lost town, shabby town, crook town. Once, very long ago, it was the choice residential district of the city, and there are still standing a few of the jigsaw Gothic mansions with wide porches and walls covered with round-end shingles and full corner bay windows with spindle turrets. They are all rooming houses now, their parquetry floors are scratched and worn through the once glossy finish and the wide sweeping staircases are dark with time and with cheap varnish laid on over generations of dirt. In the tall rooms haggard landladies bicker with shifty tenants. On the wide cool front porches, reaching their cracked shoes into the sun, and staring at nothing, sit the old men with faces like lost battles.

In and around the old houses there are flyblown restaurants and Italian fruit stands and cheap apartment houses and little candy stores where you can buy even nastier things than their candy. And there are ratty hotels where nobody except people named Smith and Jones sign the register and where the night clerk is half watchdog and half pander.

Out of the apartment houses come women who should be young but have faces like stale beer; men with pulled-down hats and quick eyes that look the street over behind the cupped hand that shields the match flame; worn intellectuals with cigarette coughs and no money in the bank; fly cops with granite faces and unwavering eyes; cokies and coke peddlers; people who look like nothing in particular and know it, and once in a while even men that actually go to work. But they come out early, when the wide cracked sidewalks are empty and still have dew on them.

The urban fabric of Bunker Hill was almost completely demolished in the 1960s under a massive redevelopment plan. For a sense of what was lost: George Mann, a Los Angeles photographer, took this picture in 1959:

Grand Avenue / 2nd Street. Photo by George Mann, courtesy of Dianne Woods and the George Mann Archives. (Fair use.)