Engage with this post on Substack.

I’ve spent some time in D.C. this year — mainly for work. I’m not quite an Acela commuter. It’s usually the more proletarian Northeast Regional. Which is fine. On the corridor, it only takes a few minutes longer between cities. You realize how compact we are in the Northeast.

Washington is the great city on the Eastern Seaboard that I’ve had the least time to explore. New York is home; Boston was, sort of, for about a year in my 20s; and Philly has been home to enough friends from Rutgers and elsewhere to almost feel like a place I’ve lived. But D.C. has remained a bit of a mystery. My visits over the years have tended to be packed with sights to see, and things to do; but it is in ordinary time that one really gets to know a place. Still, with several work meetings and a couple of evenings around hotel nights, I’ve begun to tentatively observe a few things about its urban personality.

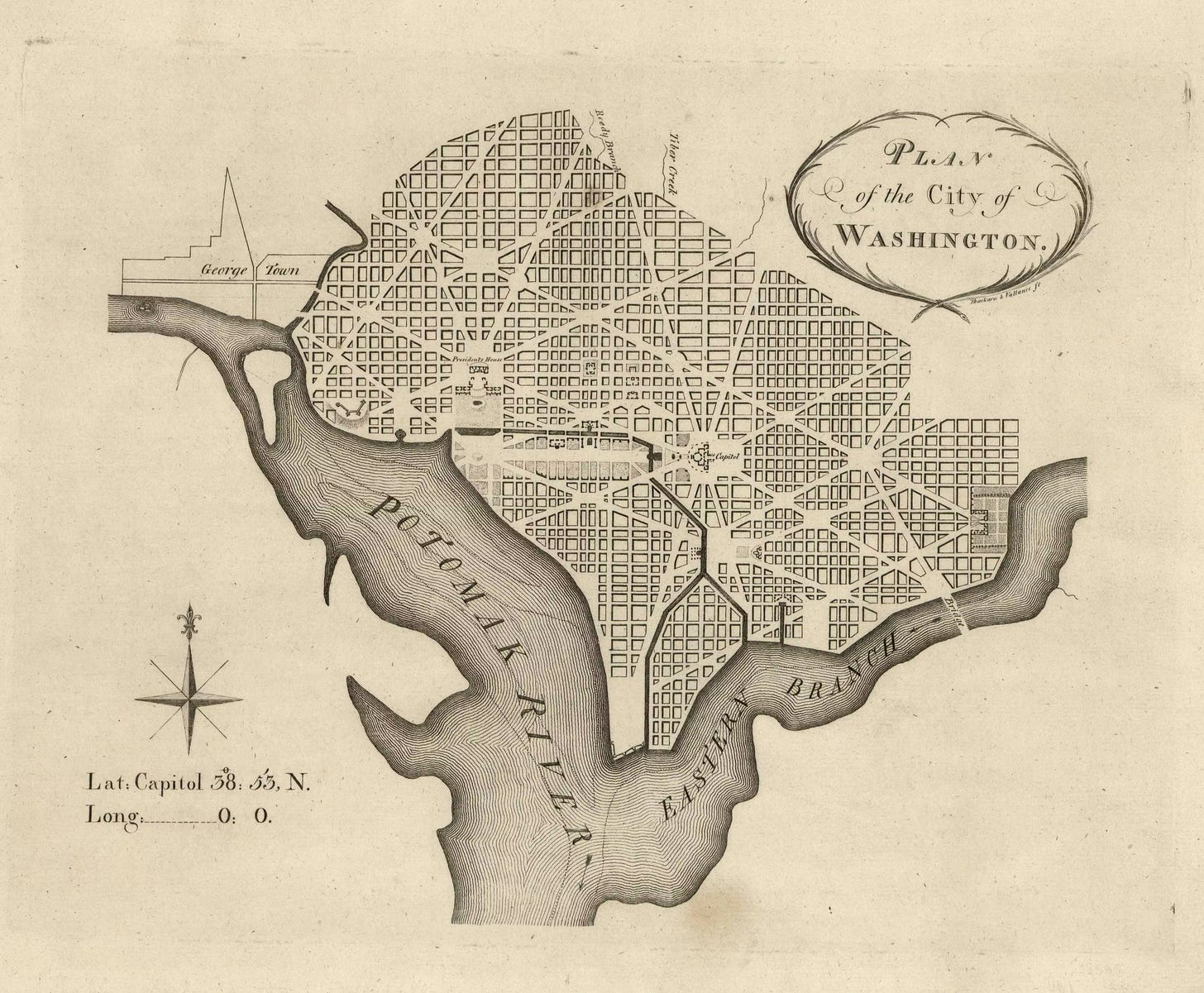

From a spatial perspective, DC’s proportions feel more like those of a European capital than a typical American city in 2025. Undoubtedly, this is due in part to L’Enfant’s many wide avenues, running off at all angles from the Capitol and the Mall; and the squares and triangles with monuments where those avenues intersect.

There is also the quirk of the city’s mandatory low skyline that has driven new development to happen in a more traditional urban pattern, with side-by-side building facades forming continuous street walls. In its details, the city is quite a bit more American — the chain stores, the people — but its massing has a certain quality that is reminiscent of Madrid or, or a district like Prati, in Rome.

There is a lot of housing being built. Right now, this is especially true in the blocks north, west, and east of Union Station. An entirely new urban fabric is being assembled, one lot at a time, that is quite impressive. If only New York City could remember how to build like this, we might not have such a housing crisis. (A century ago, it did, in Harlem and the Bronx.)

It seems that the area — which straddles NoMa and the Near Northeast — was largely composed of small row houses until the past decade; and many of these old homes, as well as vacant lots, are now being replaced with large apartment houses in a pattern that mirrors a traditional urban process. (That said, the transformation is being managed by heavy regulation — contrary to traditional urbanism).

As a cumulative effect of these changes, the area called NoMa is beginning to show massing patterns that resemble the older urban core, to the west (i.e., Metro Center, Downtown, Adams Morgan) — defined by 8-12 story buildings, attached into continuous street walls, and sustaining strips of ground-floor retail that opens onto the sidewalk. The architecture is, of course, nontraditional. East of the tracks, the Near Northeast has a bit further to go before the new development congeals.

It is an interesting city to explore. Will share a few more images:

LegalTowns is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber via Substack.